Why employees hesitate to speak up at work — and how to encourage them

(Unsplash)

Kyle Brykman, University of Windsor and Jana Raver, Queen’s University, Ontario

Imagine this: You notice a problem that might be disastrous for your company’s reputation, or you have an idea that can save thousands of dollars.

You want to say something but you’re not sure if you should. You’re afraid it might not go over well and not sure it will make a difference. You want to speak up, but you’re uncertain about how to voice your ideas in such a way that people will actually listen.

You’re not alone. Studies consistently show that employees are reluctant to speak up, and are even hardwired to remain silent, with 50 per cent of employees keeping quiet at work. Why is this the case, and how can we help people voice their opinions at work more effectively?

Speak up or zip it?

Employee voice — speaking up with ideas, concerns, opinions or information — is vital for organizational performance and innovation. On the flip side, silence is at the root of many well-known organizational disasters.

For example, Canada’s Phoenix pay system debacle, which has already cost the federal government $1.5 billion, was attributed to a culture that “does not reward those who share negative news.” Employees who sounded alarms were told they weren’t being “team players.”

Employee voice is the antidote to this culture of silence, but it’s not easy to encourage. Employees withhold voice because they think it will not be heard or fear it may backfire by embarrassing their managers or damaging their own reputations. These reservations are reasonable.

Although speaking up is generally linked with positive career outcomes, it can lead to lower social status at the office and lessened performance ratings in some circumstances.

Employees’ proactive personalities and managers’ demonstrated openness are both relevant to overcoming these reservations. Although we can’t change someone’s personality, leaders can create more welcoming environments that support and encourage voice.

Encouraging workers to voice opinions

For example, employees are more likely to speak up when they believe their leader encourages and solicits their opinions. By contrast, when leaders punish employees who dare to speak up with concerns or ideas, such as by publicly reprimanding them, voice dwindles quickly.

Pointing out others’ mistakes or sharing ideas that go against common practice can “rock the boat.” So how can employees still find ways to speak up effectively and have their ideas actually heard, despite these risks?

(Mika Baumeister/Unsplash)

Our research sought to answer this question by focusing on the quality of the messages that employees express. We first unpacked the meaning of what we call high-quality voice, uncovering the key ways that employees can improve their messages to gain greater recognition. We investigated these ideas with five studies involving nearly 1,500 participants.

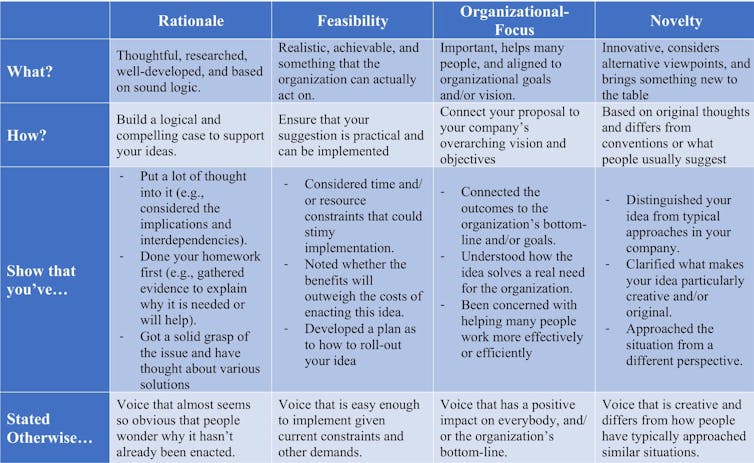

We identified four critical features of employee voice attempts that make them higher-quality:

They have a strong rationale. Their ideas and opinions are logical and based on evidence. Employees should do their homework first and build a compelling case for their ideas by showing they’ve put a lot of thought into them. They shouldn’t speak up if they haven’t gathered information or reflected on the reason behind implementing their ideas first.

They have a high feasibility. Their ideas are practical and have the potential to be implemented. Employees should consider whether their organizations can realistically take action on their suggestions, such as by accounting for time or resource constraints and offering details on how to enact them. Employees shouldn’t ignore the realities and difficulties leaders face in actually doing something with their ideas and concerns.

They have a strong organizational focus. Their opinions are critical to the success of the organization or team, not just personally beneficial to the employee. Workers should emphasize the collective benefits of their voice and link it with the organization’s visions, mission, and/or goals, such as by explaining how it will help the organization overall. They shouldn’t focus on issues that only affect themselves, otherwise it comes across as self-interested.

They have a high novelty. Employees are innovative and account for new perspectives or viewpoints. They should consider whether their organization has tried (or considered) this idea before and clarify what makes it particularly unique, such as by contrasting it from typical conventions or opinions. They shouldn’t just repeat old ideas or approach the situation with the same frame of mind.

(Author), Author provided

Putting effort into better ‘voicing’

Putting energy into developing higher-quality voice messages takes effort, but our research shows that it pays off. Employees who regularly presented higher-quality voice were regarded as more worthy of promotion and better all-round performers in their jobs.

(You X Ventures/Unsplash)

These positive outcomes were evaluated from both peers and managers. And these findings held up regardless of how often employees spoke up, whether the evaluator liked them or viewed them as competent. Basically, speaking up with higher-quality messages predicted job performance and promotability above and beyond all of these other factors.

So is there a downside to speaking up? Yes, if you don’t put the time and energy into making your input high-quality.

When people spoke up often with low-quality ideas, their peers reported that they were worse performers and less promotable. So speaking up can backfire if employees consume all of the airtime by frequently expressing low-quality ideas that offer little help to anyone.

The lesson? It’s worthwhile to speak up and share your ideas and concerns — and it may help your career — but if you do so, ensure that you do your homework first, reflect on the feasibility of implementation, connect the benefits to the organization and/or its employees and consider what makes it particularly novel.

How leaders can help

What can organizational leaders do to help employees voice their opinions more effectively? When asking for input, prompt with some questions. For example:

What is the logic for this idea and is there evidence to support it?

How might we actually implement it and overcome barriers?

How does this fit within the organization’s priorities and/or help other employees?

What is new about this idea that we haven’t tried before?

These questions can produce higher quality ideas that will benefit employees, leaders and organizations alike.

Ultimately, increasing the quality of employee feedback and opinions will help them be heard. It will also result in ideas that are more likely to be implemented and improve work conditions and performance for the entire organization.![]()

Kyle Brykman, Assistant Professor of Management, University of Windsor and Jana Raver, E. Marie Shantz Professor of Organizational Behaviour, Queen’s University, Ontario

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.